After Changing the Way Medicine is Practiced, Henrietta Lacks' Family Finally Got Their Money

- Hazel Trice-Edney

- Aug 10, 2023

- 3 min read

The descendants of Henrietta Lacks on Tuesday, August 8, 2023, said they reached an agreement with Thermo Fisher Scientific, a company that sold HeLa Cells, taken from Lacks' body, that was cloned and sold in aggregate for billions of dollars.

The settlement's details remain confidential, but Lacks’ grandchildren, who were part of the suit, seemed pleased with the agreement. The settlement was announced on what would have been Lacks’ 103rd birthday. She was born on August 2, 1920, and died on October 4, 1951. Lacks was initially buried in an unmarked grave.

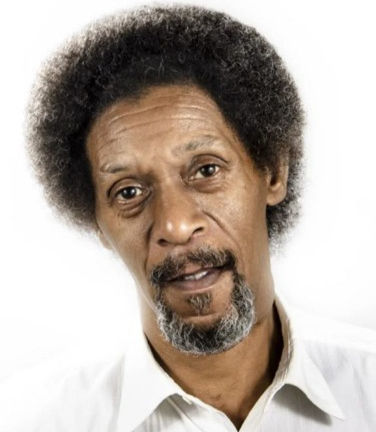

“There couldn’t have been a more fitting day for her to have justice, for her family to have relief,” her grandson Alfred Lacks Carter Jr. said. “It was a long fight — over 70 years — and Henrietta Lacks gets her day.”

The settlement was reached after daylong negotiations in a federal court in Baltimore. The lawsuit stems from the Lacks family's allegations that the cells collected from Lacks' body following her death were taken and used for medical research without her permission. Astonishingly, her cells are still in use for research purposes today. The family claimed HeLa Cells were used by Thermo Fisher to enrich their profits. Last year, the company reported second-quarter earnings of $10.60 billion.

The Lacks family sued Thermo Fisher in 2021 for profiting from what they called a racist medical system. The cells taken from Lacks became the HeLa cell line, the first human cells to be successfully cloned. They represented a critical development in medical research.

HeLa cells went on to become a cornerstone of modern medicine, enabling countless scientific and medical innovations, including the development of the polio vaccine, genetic mapping, HIV AIDS medications, treatment of cancer, and COVID-19 vaccines. About 55 million tons of the cells have been used in over 75,000 scientific studies worldwide.

Lacks or her family never knew about HeLa cells, and they were never compensated. At the time the cells were first collected in 1951, no permission was required to take the cells.

“The exploitation of Henrietta Lacks represents the unfortunately common struggle experienced by Black people throughout history,” the complaint from her descendants read. “Too often, the history of medical experimentation in the United States has been the history of medical racism.”

Another incident of medical exploitation occurred in the Tuskegee Study which examined untreated syphilis among Black men between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 400 Black men were relegated to control groups in the study and suffered from the ravages of syphilis although an effective treatment for the disease became available.

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who represented the Lacks family during the lawsuit, said Lacks was racked with pain until the end of her life as a repercussion of the procedures employed by John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. He blasted Johns Hopkins for using Lacks – and other Black women – as 'lab rats,' and said the experience was something many Black Americans could relate to.

Though Johns Hopkins has never profited from HeLa cells, according to Crump Thermo Fisher knowingly sought the rights to products that use Lacks’ cells despite her never giving consent for the cells to be taken. Thermo Fisher attempted to have the lawsuit dismissed when it was filed, arguing the statute of limitations had expired, but the family countered that the company has been profiting from the cells all this time.

Lacks’ story gained attention in 2010 when Rebecca Skloot published “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” In 2017, Oprah Winfrey starred in an HBO movie of the same name based on the book.

Comments